Pam nad yw eich ôl troed dŵr yn berthnasol

haveseen/Shutterstock

01 Hydref 2018

Yn ysgrifennu yn The Conversation, mae Judith Thornton o Sefydliad y Gwyddorau Biolegol, Amgylcheddol a Gwledig yn trafod sut mae olion traed yn achosi i bobl feddwl am yr effaith y maent yn ei chael, ond nid yw'r gyfatebiaeth yn gweithio ar gyfer dŵr:

Three thousand litres of water – that is the amount needed to produce the food each British person eats every day.

This is the opening line of a recent article also published on The Conversation. The piece reports on research published in Nature Sustainability, which investigated the water footprint of diets in three EU countries, considered national and regional differences, and comes to the overall conclusion that a healthy diet that is low in meat would significantly decrease our water footprint.

The scientific consensus is that eating less meat is a good way of reducing your carbon footprint (a measure of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere by a person’s activities) and contribution to climate change. According to the Water Footprint Network, the water footprint of a kilo of beef is 15,415 litres, compared to 322 litres for a kilo of vegetables. When compared to domestic water use (each person in the UK uses about 150 litres of water per day) these numbers seem large and worrying. But the reality is that the concept of footprints cannot be used for water in a way that is environmentally meaningful.

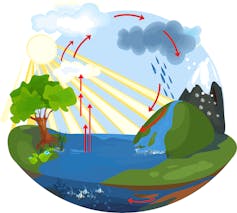

The first flaw in the water footprint concept stems from the fact that water is renewable. It can exist in lakes, rivers and the sea, below ground, as vapour in the air, in glaciers, and more. We neither create nor destroy water, it simply moves around the hydrological cycle. Water that we use in the present can also be used in the future. It isn’t going to run out in any permanent sense unless it is irretrievably polluted, or becomes incorporated into a glacier which will exist for millennia to come. So, regardless of how much steak you eat, the world is not going to run out of water.

The next problem with the water footprint concept is that it causes us to value water as being equally important wherever it is. But it’s fairly obvious that a thousand litres of freshwater in Wales is not of equal value to a thousand litres of water in a desert.

In addition, there is no clear relationship between the volume of water we use and the environmental impact of using that volume. So, although with carbon emissions we can reliably say that a serving of pulses contributes less to climate change than a serving of beef, we cannot be nearly so confident when comparing the environmental impacts of the water used to produce the two products.

Hydrologists express these issues of time and place using diagrams and equations known as water balances. Water exists in stocks, and flows occur between them. Measuring the size of each stock and flow allows us to understand what the consequences might be of changing flow rates into/out of stocks, or diverting flows in some way, with reference to a specific time period.

This helps us understand another problem with the water footprint concept. The footprint is defined as the volume withdrawn from a stock, minus the amount that is discharged back into that stock. When rain falls on grassland, much of it is taken up by plant roots, moves upwards through the stem and then evaporates from the leaves. If the grass is eaten by cattle, then the water footprint of the beef includes all this water. But if the rain was to fall on an area of forest rather than grassland, evapotranspiration (the process by which water evaporates from plant leaves and from the ground) would be higher.

Trees take up more water than grass, so trees have a large water footprint. Does this make forests bad? Clearly not. Evapotranspiration is simply a flow within the hydrological cycle, it is no better or worse in environmental terms than the rainwater that flows into streams and rivers.

However, this way of calculating water footprints also means that if a water company withdrew 1,000 litres of water for domestic water use from a river, and then discharged it back into the river after it had undergone sewage treatment, the water footprint is zero. The water has become immediately available again at local level.

Evidently, water footprints lack scientific validity, and don’t actually tell us anything very useful about the environmental impact of water use – but what can we do instead? The Alliance for Water Stewardship is promoting a promising initiative that considers industry and location-specific measures, such as whether water is being abstracted from an aquifer (an underground layer of permeable rock that holds water) at an unsustainable rate, whether irrigation schemes are necessary and properly controlled, and how to balance the needs of all water users in the area. However, these schemes are not yet widely adopted, and it remains difficult for consumers to make water conscious choices.

There is also a risk of worrying about water at the expense of other environmental issues. The effects of climate change are felt most immediately through water-related events such as droughts and floods, but we would do well to remember that these events are symptoms and it is the cause that we need to address.![]()

Judith Thornton, Low Carbon Manager (BEACON), Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.