Achubwyd 10,000 o blant yn Kindertransport 1938 ond mae'n anodd ei ddisgrifio fel llwyddiant

22 Tachwedd 2018

One of the UK’s most significant child rescue efforts began on December 1, 1938: the Kindertransport.

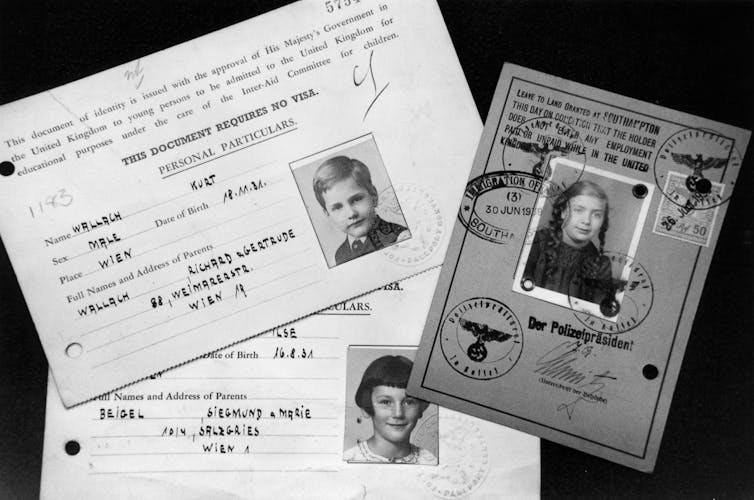

Following the November pogrom of the same year – when SA paramilitary forces and German civilians perpetrated acts of state-sponsored violence against the Jewish population, their places of worship and property – pressure built on the UK to help Jewish citizens in the German Reich. In response, the British government decided to waive visa requirements for unaccompanied minors fleeing persecution.

Aid organisations both in the UK and on the continent leapt into action, and the first “Kindertransport” arrived in the country on December 2, bringing around 200 child refugees to the UK. Overall, approximately 10,000 children and young people arrived before the scheme ended with the outbreak of World War II.

Today, the legacy of the Kindertransport is frequently discussed as a positive example of the UK’s humanitarian attitude towards refugees in the past. However, in the last 20 years, extensive research has shown that the legacy of the 1938/39 Kindertransport should be seen in a more critical light. Yes, it was a visa waiver scheme initiated by the UK government, but financial and organisational support was largely provided by charities and volunteers. It also only allowed those under the age of 17 to find refuge in the UK. Adult refugees had to meet very restrictive criteria and most applications from adults were unsuccessful.

There are a number of theories as to why the UK government restricted the visa waiver scheme to child refugees only. The decision clearly limited the numbers eligible, and children were unlikely to enter the labour market immediately, allaying fears about foreign competition for British workers. Looking at press reports from the 1930s, there was also a fear of dangerous adult individuals disguising themselves as refugees, while the Kindertransportees could be portrayed as young and innocent.

This placed continental Jewish families in a difficult dilemma. They had to decide whether to let their children – aged as young as two – travel to the UK on their own and live with foster families, or in children’s homes, in order to escape National Socialist persecution. In 1933, the League of Jewish Women discussed the issue of children emigrating unaccompanied and the general consensus seemed to be that this was not desirable. However, in 1933, Jewish citizens clearly did not anticipate the intensity of National Socialist persecution and violence that would be perpetrated against them. The events of November 1938 made families consider any means of escape, even if it meant splitting children from parents.

Most of the children who travelled to the UK on Kindertransport left their parents behind on the continent. There was a small number of orphans but most of the children had lived with their families. Memoirs and oral history interviews describe heartrending scenes when children had to part from their parents before boarding trains.

The separation experience clearly varied according to the age and upbringing of the child and the situation they found themselves in after arrival in the UK. Some of the older children felt relief when they left the German Reich, and others saw their flight as an adventure. For many smaller children, the whole experience was bewildering and frightening. It is not surprising then that some families decided separation was not a solution and did not put their children forward for a Kindertransport. As Bob Kirk, who fled from northern Germany aged 13, reflected in a recent interview: “I felt tremendous gratitude to my parents for their courage. All the parents who allowed their children to go showed tremendous courage.”

Some parents promised their children that they would follow them to the UK soon after they left. A small number did manage this by obtaining visas and, for example, taking up positions in domestic service. But even in those cases where more than one family member escaped to the UK, they were often unable to live together because of the economic and practical limitations placed on refugees.

In other cases, the children desperately tried to facilitate their parents’ escape once they themselves had arrived in the UK, but in the large majority of cases they were unable to do so. William Dieneman arrived in the UK from Berlin aged nine with his sister, his parents later managed to escape, too. But he was not able to live with his parents or sister and so told me:

What was difficult about my childhood was that we had no home, I saw my sister rarely, our family was fragmented.

There is a frustrating lack of statistical data concerning the Kindertransport, but it is now estimated that only about half of the 10,000 saw one or both of their parents again. Most others suffered the trauma of having to find out that their parents were murdered in the Holocaust. Where parents and child refugees were united after 1945, it was not usually a straightforward happy ending. In most cases, many years had elapsed and the children and parents had lost their emotional bonds and common cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

It is too simplistic to see the Kindertransport purely as a success story. Around 10,000 human lives were saved, but many paid a heavy price. Even those families that were able to reunite were often broken beyond repair.![]()

Andrea Hammel, Reader in German, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.