Ice temperatures warmer than expected on world’s highest glacier

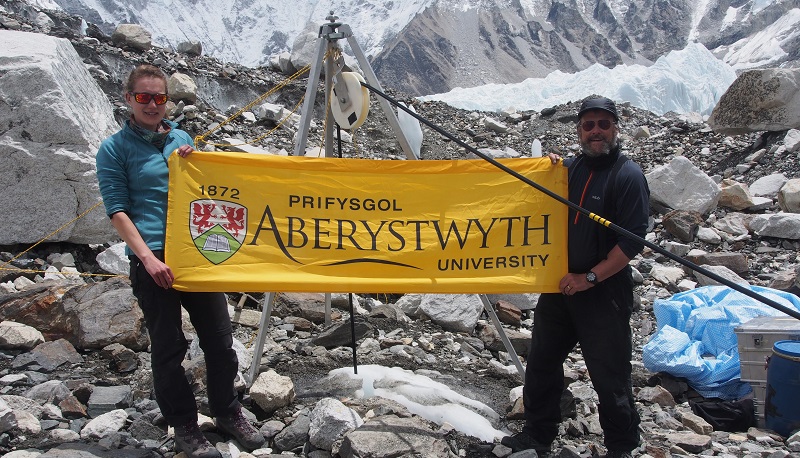

Images: Katie Miles and Professor Bryn Hubbard, picture on the Khumbu glacier in 2017.

19 November 2018

Ice temperatures inside the world’s highest glacier on the slopes of Mount Everest are warmer than expected, according to new research by glaciologists from Aberystwyth, Kathmandu, Leeds and Sheffield universities.

The findings are revealed in a paper published in Nature’s respected open-access journal, Scientific Reports.

Lead author Katie Miles and Professor Bryn Hubbard from the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth University, travelled to Khumbu Glacier, Nepal, in 2017 and 2018 as part of the EverDrill research project.

Working at heights of up to 5,000 m, PhD student Katie Miles and Professor Hubbard used a specially adapted car wash unit to drill deep into the glacial ice.

In May 2017, the team became the first to successfully drill to the base of Khumbu Glacier. They were also the first to record temperatures below the seasonally affected surface layer of the glacier.

Strings of temperature sensors, constructed with the help of Dr Samuel Doyle at Aberystwyth University, were installed into boreholes in the lower-elevation ablation area of the glacier and left to collect data for several months.

The resulting temperature measurements showed a minimum ice temperature of only −3.3 °C, with even the coldest ice being a full 2 °C warmer than the mean annual air temperature.

Katie Miles said: “Our results indicate that high-elevation Himalayan glaciers are vulnerable to even minor atmospheric warming, and there are important implications here for humans as well as the planet. Millions of people in the foothills of the Hindu Kush-Himalaya region depend on glacier melt as part of their water resources. Rising surface temperatures could lead to a decrease over the next 30 years in the volume of water melting on the glaciers and contributing to downstream water resources.”

Professor Bryn Hubbard, Director of the Centre for Glaciology at Aberystwyth University and a holder of the Queen’s Polar Medal, said: “Our work in the Himalaya builds on wider research by the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences at Aberystwyth where we have been measuring and modelling how glacial ice flows for several decades – in the Arctic and Antarctica as well as the Alps and more recently, Nepal. Understanding what actually happens inside these glaciers is critical to developing computer models to help predict their response to anticipated climate change.

“A key property of the ‘warm’ ice we have measured within Khumbu Glacier is that any additional energy input, such as from the Sun’s rays and warm air, melts that ice, producing water, which means the glacier will be especially sensitive to future climatic warming. In contrast, further energy input into ‘cold’ ice (which is at any temperature below its melting point) simply heats that ice further towards zero, producing no meltwater.”

Professor Bryn Hubbard and Miss Katie Miles are collaborating on the EverDrill project with Dr Duncan Quincey (project leader) and Dr Evan Miles from the University of Leeds, and Dr Ann Rowan from the University of Sheffield. Both Dr Quincey and Dr Rowan are alumni of Aberystwyth University’s Department of Geography and Earth Sciences.

The work is funded by the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council, NERC.