Sut sbardunwyd oes aur sinema Ciwba gan y chwyldro

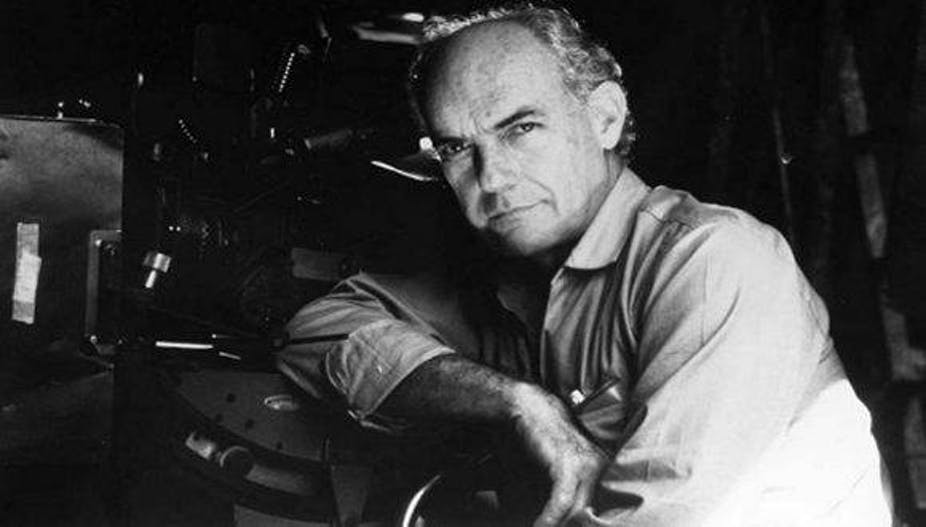

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, director of the 1968 Cuban film Memories of Underwood.

08 Ionawr 2019

When Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and the bearded guerrillas from the Sierra Maestra mountains took Cuba from dictator Fulgencio Batista in January 1959, a revolution began. Changes were seen in everything from education to health care, politics to the arts. The country became a site for social experimentation in all aspects of life – including cinema.

The formation of the the Cuban Film Institute (Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos, or ICAIC) on March 24, 1959 was the first of many new institutes designed to take back control of all Cuban life. Before the revolution, Cuba’s film industry was very small with a few notable successes, such as El Capitán Mambí (1914). But it was always dominated by large North American studios such as MGM and Warner Bros, who had a virtual monopoly over film production and distribution throughout Latin America.

It was never the aim of the ICAIC to try and replicate this silver screen success, however. It was set up to produce and disseminate a new culture, one designed to decolonise the island from its long history of Spanish and US dominance.

Cuban filmmakers found a variety of new aesthetics inspired by Soviet socialist realism, French nouvelle vague and Italian neorealism. They mixed documentary and fiction styles to deliberately blur the boundaries between fiction and reality. They went far beyond either Hollywood or European influences to write a new history of the island in celluloid.

Many of these films gained international recognition. 1968’s Memories of Underdevelopment, directed by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, is recognised as one of the top 100 films of all time by leading critics and continues to divide opinion as to its meaning. Radical, densely layered and complex, the film examines one man’s struggle to come to terms with the new Cuba in the early 1960s. A Cuba in which each citizen was asked to question their own subjective consciousness, their place and meaning in the new society.

If the 1960s was the decade of experimentation, the 1970s proved to be a problematic decade for Cuban culture generally. But while literature and theatre suffered from censorship and the imprisonment or exile of a number of prominent artists, cinema largely escaped the censors’ harsh cutting knife. Films with critical voices – such as Portrait of Teresa (1979) and One Day in November (1971) – continued to be released due to the revolutionary nature of the filmmakers themselves, as well as the nature of the medium, which was often difficult to interrogate from a political point of view.

Avant garde seriousness

Cuban filmmakers avoided Hollywood’s frivolities and focused on re-writing the country’s history in films that tackled serious subjects in often avant garde ways. They dealt with the island’s history of slavery, gender and machismo and more contemporary issues such as housing, generational differences, and exile and emigration.

As experimental cinema mostly has a limited audience, a more popular aesthetic was sought during the 1980s. Filmmakers tried to combine the seriousness of using cinema as an art form, and not simply for entertainment, with content that would speak to the average Cuban. Social satire became commonplace and films such as Plaf! Or Too Afraid of Life (1988) and Up to a Certain Point (1983) reached audiences of up to two million, at a time when the island’s population was 9.7 million. The 1990s was a difficult decade for Cuba generally. The collapse of the Soviet Union brought to an end the economic and ideological support that had helped sustain the revolution for 30 years. Many predicted the end of the revolution itself, but it survived through what was euphemistically called the “Special Period in Peacetime”. The Cuban film institute lived on too – but with some changes, mainly linked with the necessity for co-productions with foreign production companies.

Cuba’s colonial past and the Communist revolution have left a lasting imprint on the country’s society. Yet there is a tangible sense of change on the island again, since President Miguel Díaz Canel was elected in April 2018. This has been reflected in the national cinema too. Cuba is moving into the digital age and film is one of the drivers of this progress.

Internet access is still limited but cheaper digital production methods have supported the efficacy and global reach of Cuban filmmakers. Their work, somewhat in lieu of adequate distribution and traditional screening facilities, is often disseminated via “flash” (USB memory sticks). This DIY attitude is typical of the resourcefulness of a people who have lived through years of economic challenges.

Taking advantage of the digital world, Cuban cinema today, while still having strong roots within the national film institute, is still a source of social criticism. Films do sometimes still suffer at the hands of the censors, and there is the constant struggle between the government and the filmmakers to officially allow independent production on the island. But while all this goes on Cuba’s filmmakers keep on making and somehow – any how – distributing their films. Although today it is a different national cinema from 60 years ago, it is still revolutionary.![]()

Guy Baron, Senior Lecturer in Spanish, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.