Mae myfyrwyr y DU yn cefnu ar ddysgu iaith, felly rydym yn chwilio am ddull mwy creadigol

Maxx-Studio/Shutterstock

05 Mai 2023

Mewn erthygl yn The Conversation mae Dr Alex Mangold o’r Adran Ieithoedd Modern yn trafod y gostyngiad yn y nifer sy'n manteisio ar ieithoedd modern mewn addysg uwch a sut gall fwy o greadigrwydd yn y pwnc helpu i wneud dysgu iaith yn fwy deniadol.

There is a storm brewing for modern language education in the UK. The uptake in higher education has more than halved in the past 15 years. And in the same period, ten modern language university departments have closed, while a further nine have been significantly downsized.

Meanwhile, language provision in schools is patchy. There are substantial regional differences, and only half of pupils in England learn a language at GCSE level. Together, these issues have created an overall problem with access to language learning.

Given these challenges, as language lecturers we believe the way we teach and assess modern languages in our universities needs a rethink. That’s why we want to explore how more creativity in the subject could help to make language learning more attractive and sustainable in the future.

Despite numbers that suggest an overall sector decline, current trends indicate that it is mostly single honours studies with one language and traditional language choices such as German, French, Italian and Spanish that are affected by dwindling numbers. Combination degrees, especially with non-European languages, appear to be relatively stable.

So, departments offering single language degree combinations and more traditional languages could see these trends as an opportunity to reevaluate their approach.

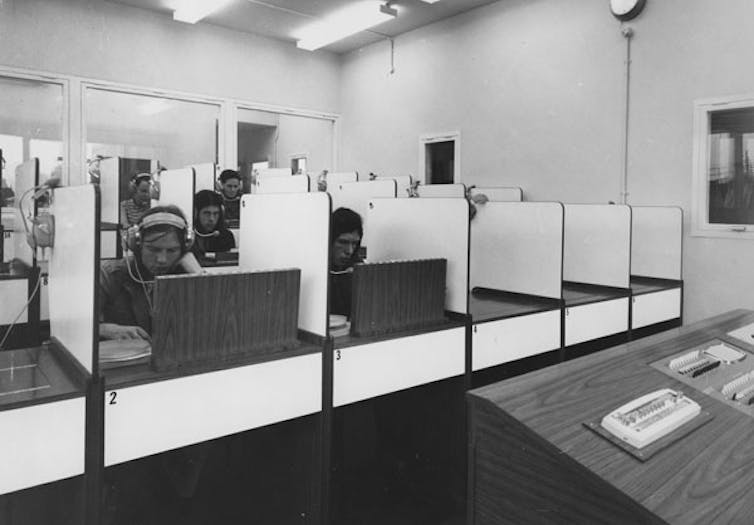

In higher education, traditional language teaching and assessment methods involve continuous assessment in four typical language learning areas: grammar, translation, listening and oral. On top of that, there is presentation and essay work, as well as oral and written exams.

Traditional language testing relies on memorisation of vocabulary or grammar to measure student performance. In contrast, feedback-based assessment in the form of written language tasks or translation can have a positive effect that goes beyond a person’s limited ability to use the language in pre-defined contexts. But it is also very subjective and time-consuming.

In addition, artificial intelligence software such as ChatGPT, which generates detailed written answers to questions, or Deep L, which can translate texts with high accuracy, make take-home written assignments vulnerable to cheating, plagiarism and superficial learning.

Neither memorisation or feedback-based testing encourages students to apply their language learning to real-life situations. Language is more complex than simple memorisation, translation tasks or essay writing.

An alternative approach that is rarely used in language learning would be to include more creativity in assessment. Creative assessment in modern languages can be any artistically-inspired exercise aimed at measuring a student’s performance.

Examples of artistic research and creative assessment could include blog writing, podcasts, animation and art installations, creating graphic novels, writing poetry, painting, photography and even clowning.

If a student were to write and direct a short film based on women’s writing in Latin America, it could provide lecturers with endless opportunities for creative, task-specific and more individualised feedback that is less repetitive. It would also provide a productive opening for more student group work, for critical reflection that goes beyond simple essay questions and could add valuable skills to a student’s CV.

Currently, creative assessments are mostly limited to theatre and art schools or to creative writing departments. We argue that ignoring such an approach in our subject area diminishes the potential cultural, subjective and creative value of modern languages because it neglects opportunities for intercultural, social and artistic exploration.

We already know that being more creative improves learning in general. Plenty of research has been done looking at how creativity improves academic outcomes across age ranges and topics, including language learning.

We think such findings should be applied practically to language learning to encourage students to approach their studies in different, more interesting ways. And this could ultimately inspire more students to study modern languages at university. Given the significant decline language teaching is facing, it’s vital that we look for and test such approaches.

Creativity

As a start, we’ve launched the Creative Modern Languages project. It’s an initiative that provides university researchers, students and teachers with an open-access modern languages hub. We are hoping that it will help to identify the best examples of creativity in language learning and act as a catalyst for more creative types of teaching, assessment and research.

There are some caveats, however. We acknowledge that implementing such changes may be met with fears and restrictions. Some colleagues say they are worried about time constraints and the administrative burden that may come with introducing creative assessment. They have also expressed concerns about not feeling creative enough, a lack of funding and increased workload.

But it is clear to us that implementing more creative forms of research and assessment in modern languages is necessary for attracting students in the future and countering the potential negative effects of AI technology.

What we are hoping to do is to encourage an ongoing discussion about more creative types of research and assessment in modern languages. Ultimately, it could help to introduce more students to the joys of other languages, people and cultures.![]()

Mae'r erthygl hon wedi ei hailgyhoeddi o The Conversation dan drwydded Creative Commons. Darllenwch yr erthygl wreiddiol.