Melting of Alaskan glaciers accelerating faster than thought

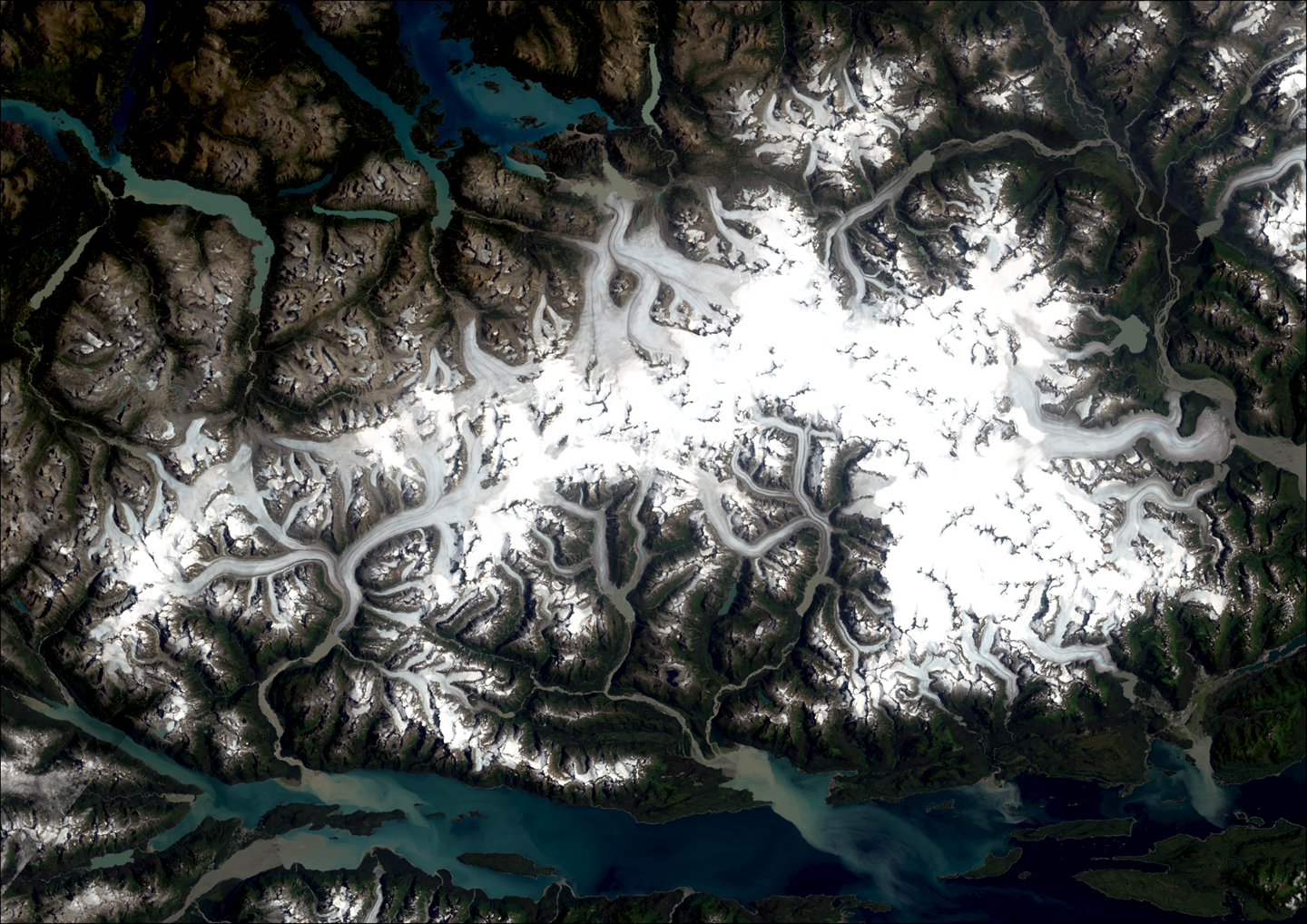

Satellite Image of Juneau Icefield Credit: Landsat imagery courtesy of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and U.S. Geological Survey

02 July 2024

Melting of glaciers in a major Alaskan icefield has accelerated and could reach an irreversible tipping point earlier than previously thought, new research suggests.

The research, involving scientists at Aberystwyth University in Wales, found that glacier loss on Juneau Icefield, which straddles the boundary between Alaska and British Columbia, Canada, has increased dramatically since 2010.

The team, which also included universities in the UK, USA and Europe, looked at records going back to 1770 and identified three distinct periods in how icefield volume changed.

They found that glacier loss remained consistent between 1770 and 1979 with up to 1 square kilometre lost a year – this had increased to over 3 square kilometres a year in the period 1979 to 2010.

Between 2010-2020 there was a sharp acceleration when the rate of ice loss doubled, reaching almost 6 square kilometres a year.

The research, published in Nature Communications, found that icefield-wide rates of glacier area shrinkage were five times faster between 2015 to 2019 than the 1948-1979 period.

Overall, the Juneau icefield lost a quarter of its original volume in the 250 years between 1770 and 2020.

This faster thinning of the glacier has been accompanied by increased glacier fragmentation.

The team mapped a dramatic increase in disconnections, where the lower parts of a glacier become separated from the upper parts.

100% of glaciers mapped in 2019 have receded compared to their position in 1770, and 108 glaciers have disappeared completely.

Alaska contains some of the world’s largest plateau icefields and their melting is a major contributor to current sea level rise.

Dr Tom Holt from Aberystwyth University said:

“It is really concerning to see the rapid and accelerating loss of glaciers from the Juneau Icefield.

“We know that climate-driven ice loss from glaciers and icefields contributes to rising global sea-levels. And Alaska is expected to remain the largest regional contributor to rising sea levels up to the year 2100.

“What this research highlights is that we have been under-estimating the amount of ice being lost from this particular icefield, which may also be the case for others located in the Arctic.

“The reduction in icefield area also seems to be contributing to a positive feedback loop: as the glaciers melt, their surfaces become darker as rock debris is exposed, reducing solar reflectivity – and increasing surface melt -further contributing to the loss of the glaciers.”

The researchers think the processes they observed at Juneau are likely to affect other, similar icefields elsewhere across Alaska and Canada, as well as Greenland, Norway and other high-Arctic locations.

They also say current published projections for the Juneau icefield that suggest ice volume loss will be linear until 2040, accelerating only after 2070, may need to be updated to reflect the processes detailed in this latest study.

Study lead, Dr Bethan Davies, Senior Lecturer, Newcastle University, added:

“It’s incredibly worrying that our research found a rapid acceleration since the early 21st century in the rate of glacier loss across the Juneau icefield.

“Alaskan icefields – which are predominantly flat, plateau icefields - are particularly vulnerable to accelerated melt as the climate warms since ice loss happens across the whole surface, meaning a much greater area is affected. Additionally, flatter ice caps and icefields cannot retreat to higher elevations and find a new equilibrium.

“As glacier thinning on the Juneau plateau continues and ice retreats to lower levels and warmer air, the feedback processes this sets in motion is likely to prevent future glacier regrowth, potentially pushing glaciers beyond a tipping point into irreversible recession.”

“This work has shown that different processes can accelerate melt, which means that current glacier projections may be too small and underestimate glacier melt in the future.”

The team used a combination of historical glacier inventory records, 20th century archival aerial photographs, and satellite imagery as well as geomorphological mapping conducted during fieldwork in 2022 to piece together a comprehensive picture of changes over the past 250 years.