Antibiotic pollution makes snails forgetful by altering their gut microbiome

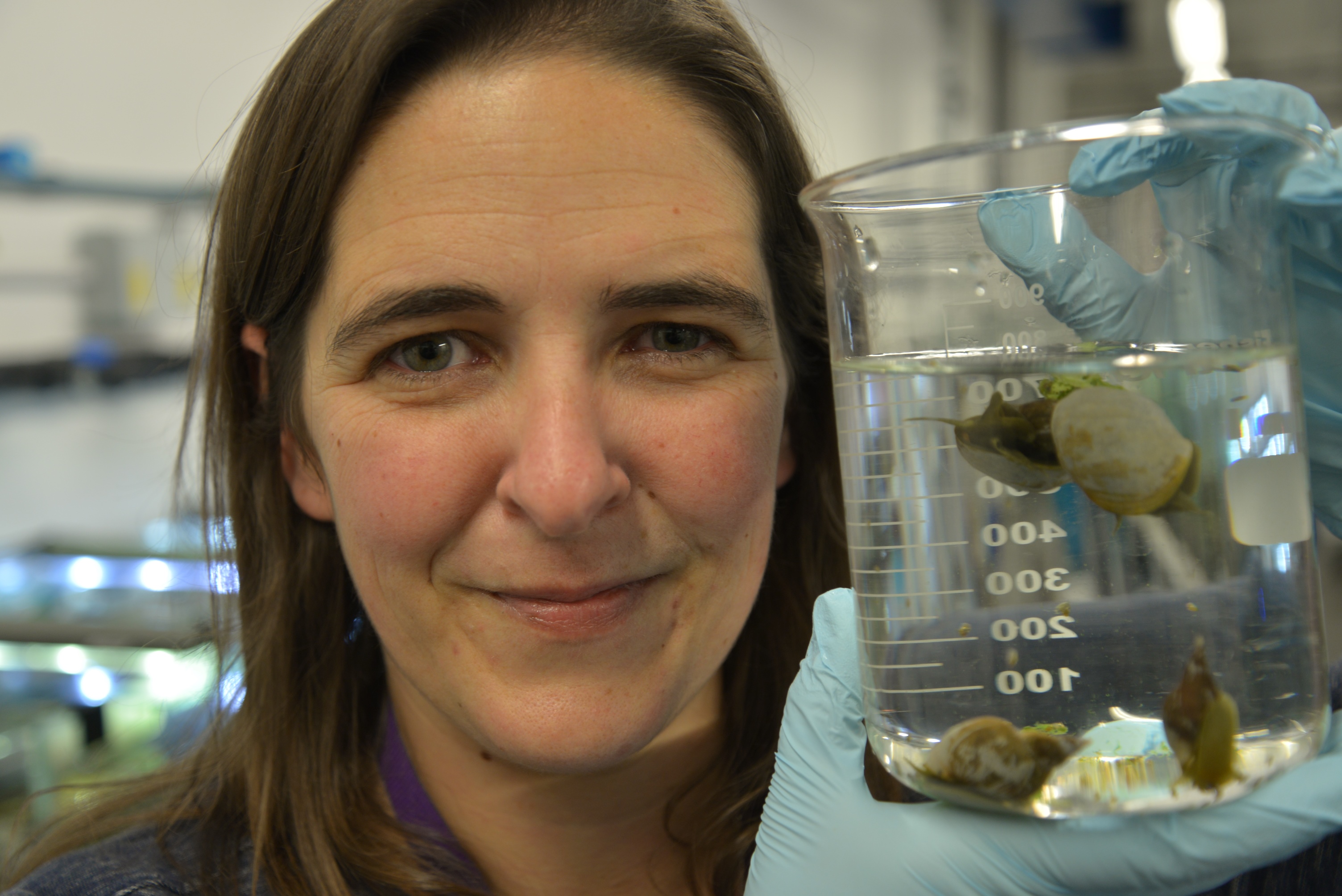

Dr Sarah Dalesman, Aberystwyth University

30 May 2024

Antibiotics prevent snails from forming new memories by disrupting their gut microbiome - the community of beneficial bacteria found in their guts.

The new research, led by the University of East Anglia (UEA) in collaboration with Aberystwyth University, highlights the damaging effects that pollution could be having on aquatic wildlife.

In the study, pond snails were given a favourite food – carrot juice – but had to quickly learn and remember that it was no longer safe to eat.

Snails in clean water did well, avoiding feeding on the carrot juice when it had been paired with a chemical they dislike.

However, snails that had been exposed to high concentrations of antibiotics in the water failed to learn and form memory and continued to show normal feeding behaviour even after training.

Co-author Dr Sarah Dalesman from Aberystwyth University’s Department of Life Sciences said:

“Wastewater entering our streams and rivers contains a cocktail of chemicals used to treat humans and animals. However, we still don’t know how many of these chemicals are affecting the animals living in freshwater environments.

“Our research aimed to determine if the gut microbiome of aquatic animals can be altered by antibiotic pollution and if this could be detrimental to their survival”.

Lead author Dr Gabrielle Davidson, of UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, said:

“It’s well known that a healthy gut microbiome is important to human health, and our study is the first to show this is also the case in snails."

The researchers found the antibiotics altered the gut microbiome substantially and changed the abundance of bacteria that have been found to relate to healthy memory formation in other animals, including humans.

This relationship between the bacteria found in the gut and brain function is called the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Chemicals produced by the good gut bacteria when breaking down food can improve brain health and cognitive function.

Reducing the abundance of these healthy bacteria in the gut prevents the gut microbiomes’ otherwise beneficial effects on the brain.

Previous studies on the link between the gut microbiome and brain function have focused on terrestrial species. However, aquatic wildlife is more likely to be directly impacted by antibiotic exposure in the environment.

Antibiotics are not removed effectively by waste treatment, and so enter the freshwater environment.

The antibiotic concentrations snails were exposed to in the experiment were at similar levels detected in freshwater in the UK, Europe and globally.

If freshwater pollution prevents snails from having a healthy microbiome, they won’t be able to use their brains to adjust their behaviour when they encounter new information.

Dr Sarah Dalesman said: “Previous research has found pond snails have to learn about predators, what is good or bad to eat, and even remember who they have mated with.

“Anything that interferes with their memory will reduce their survival.”

The researchers say this is especially worrying in the face of the many new environmental challenges animals experience from human activities.

Dr Davidson added: “If we find this effect in snails, it is highly likely that antibiotics are having similar effects on other aquatic animals.

“We hope this study prompts greater emphasis on the importance of healthy gut microbiomes for wildlife and increases efforts to reduce the chemicals entering our environment.”

The study was funded by the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour.

‘Antibiotic-altered gut microbiota explain plasticity in host memory and disrupt the covariation of pace-of-life traits in an aquatic snail’ is published in The ISME Journal: Multidisciplinary Journal of Microbial Ecology.

This research was carried out in accordance with the ASAB (Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour) Guidelines for the Treatment of Animals in Behavioural Research and Teaching.