Toxoplasma 'cat poo' parasite infects billions – so why is it so hard to study?

New Africa/Shutterstock

23 September 2019

What if I told you that there is a good chance you are carrying a parasite that is transmitted through cat poo? Two billion people around the world carry Toxoplasma gondii so there may be more than a 25% chance that it is in your body too.

Toxoplasma is closely related to Plasmodium, the parasite that causes malaria. But while Plasmodium is quite fussy about where it lives, only able to survive in liver cells and then in red blood cells, Toxoplasma doesn’t much care. It muscles its way into just about any type of cell.

But it’s also very hard to isolate Toxoplasma from the cells that it infects. So I’m trying to find a method to increase the amount of Toxoplasma parasite in samples. This will allow scientists to have better quality samples to investigate how the parasite spreads and look for ways to treat it.

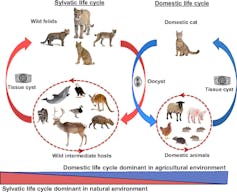

In some parts of Europe, such as France, around 50% of the population play host to the parasite. Once infected, you will never get rid of your new silent buddy. But humans are not actually the parasite’s natural host. Normally it cycles between cats – both domestic and wild – and the animals they eat.

Cats release the equivalent of Toxoplasma eggs, known as oocysts, in their faeces. These oocysts can wait in the ground for many years before they are picked up by animals such as mice, birds or even crocodiles. In their new host, the oocysts breed and move through the body and look for a cell to make their new home. There they will wait quietly for years, until their host is eaten by a cat. Once inside their final host, the parasite wakes up again and starts dividing.

It’s not only through cat faeces that humans can become infected, however. In fact, the most common method of infection is through consuming undercooked or rare meat containing the parasite. Infection can also happen in the womb, or through an organ transplant from an infected person.

Read more: Toxoplasmosis: how feral cats kill wildlife without lifting a paw

At worst, a typical Toxoplasma infection (known as toxoplasmosis) feels like a light flu. The parasite doesn’t want to kill its intermediate host (us) after all. It’s only when the oocyst begins to falter – when it can no longer get into its final host – that it become dangerous.

It can be particularly dangerous for a woman to get toxoplasmosis during pregnancy. A developing infant is protected only by its mothers’ antibodies that cross the placenta. But the mother’s T cells (the body’s most effective weapons against bacteria and parasites) can’t cross into the foetus. This is because T cells would act as if the developing child were a huge parasite and destroy it.

Maternal antibodies do a good job against a flu virus, but can’t protect against Toxoplasma. For Toxoplasma, the foetus would need its own inflammatory T cells to drive the parasites back into their oocysts. But foetuses don’t have their own T cells either. So if the parasite managed to pass from mother to baby it would reproduce widely and multiply until it caused brain damage.

Investigating effects

Due to this unique behaviour, Toxoplasma has been widely investigated by parasitologists, biologists and psychiatrists. Researchers have found that the Toxoplasma parasites may affect human behaviour and personality, for example. Studies have also suggested a link with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Further research has also shown that infected men have a tendency to disregard rules, and that they are more suspicious and jealous. In women, the shift in these two factors is the opposite. They appear to be more warm-hearted, outgoing and easygoing than women without the parasite.

Another study found that students infected with Toxoplasma were 40% more likely to major in business at university, and 70% more likely to emphasise “management and entrepreneurship” in their business studies.

Read more: Is the brain parasite _Toxoplasma_ manipulating your behavior, or is your immune system to blame?

While scientists are currently trying to find out more about how the parasite affects people, however, they face a critical problem. It is very difficult to isolate Toxoplasma from human DNA, and the parasite can only grow within other living cells. So unlike bacteria, it cannot be easily cultured in the lab.

In addition, unlike many other disease-causing microbes, Toxoplasma is typically found in very low numbers within clinical samples. So when a sample is purified, the vast majority of DNA in it will come from the patient rather than the parasite.

My current research is focused on increasing the number of parasites to obtain high quality samples. It might seem counter-intuitive to try to increase the amount of parasites, but it is important that we get a large number of them in different samples for comparison. To amplify the target Toxoplasma’s DNA, I am using a new technique called selective whole genome amplification to increase the number of parasites in a sample more than 100 times.

My ultimate aim is to analyse the parasite’s DNA and compare samples found in the UK with samples from across Europe and around the world. This will hopefully shed light on what the common sources of infection are in the UK population, and improve our understanding of the epidemiology and virulence of this important human pathogen. And will assist in developing new treatments, methods of surveillance and strategies to stop people getting infected.![]()

Justyna Anna Nalepa-Grajcar, PhD Researcher, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.