Dot and Billy: how love letters document the stories of lives torn apart by World War 1

Sending my love. Agnes Kantaruk/Shutterstock

09 November 2018

Writing in The Conversation, Dr Sian Nicholas from the Department of History and Welsh History discusses how love letters document the stories of lives torn apart in World War 1:

During World War I, the only way to keep in touch with loved ones who were serving in the armed forces was through letters. Sent back and forth over periods of months or even years, they tell the day-to-day stories of soldiers’ lives and those of the people they had left behind. We are fortunate that so many of these letters were kept and treasured to this day so that we can retell their tales.

I have been working on the Heritage Lottery Fund-sponsored community project, Aberystwyth at War 1914-1919: Experience, Impact, Legacy, to bring some of the town’s war stories back to life using letters and other evidence. One of the most intriguing that we have uncovered so far is that of Billy and Dot, an army captain and a university student who sent each other love letters during his deployment.

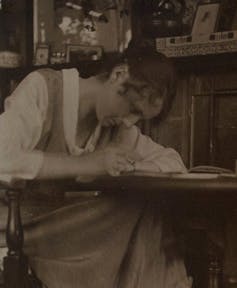

Stanley Wilbrahim Burditt (“Billy”) was a captain in the Cheshire Regiment, who spent part of 1915 in camp in Aberystwyth, on the coast of west Wales. Agnes Dorothy French (“Dot”) was a undergraduate student at the University College of Wales, Aberystwyth. They appear to have met at a series of social gatherings arranged between the visiting officers and female undergraduates. When the Cheshires left Aberystwyth for France in July 1915, Dot promised to write to Billy. Their wartime correspondence, comprising more than 170 letters, provides a personal insight into two young people whose lives were irrevocably shaped by the war.

Billy and Dot’s love story was a complicated one. Billy was clearly besotted from the start. Dot’s early letters are affectionate but light-hearted. When in February 1917 Billy openly declares his love for her, Dot’s response is raw in its confusion and honesty. She had no idea he felt that way, indeed would never have written in that tone if she had. She is uncertain of her own feelings – she is desperate to remain friends – but she fears to make promises she can’t keep.

Billy is duly apologetic in turn, and Dot agrees to be his “fiancée pendant la guerre” (“girlfriend for the duration”). As the letters continue into the summer of 1917, Billy’s feelings persist and Dot’s soften. By July they are both desperate for Billy to come home on leave so they can meet again and assess their feelings. For, as Dot notes, she has never actually seen him out of uniform. He finally gets home leave in late August and they spend two chaste but emotionally intense days together. They begin to plan their future. On September 30 Billy is killed by a German bomb.

Through their letters the correspondents’ characters shine through. Dot’s are open and impulsive; Billy’s are solicitous and romantic. The early letters talk a lot about the books they have read and the plays they have seen, as they find interests and tastes in common (Peter Pan is a constant reference point). Dot’s letters recount in self-deprecating detail her wartime life as, first, an ill-fated voluntary aid detachment (VAD) nurse (she is invalided out after contracting scarlet fever), and then a sadly disorganised schoolteacher.

Billy’s letters are more serious and lyrical, seeking to describe and make order of the world around him, from his “Bairnsfather” farmhouse billet, to – in one striking passage – a “Nevinson” scene of a German plane pinpointed in a black night sky by British searchlights, reminiscent of the artist’s depictions of the horrors of modern war. And throughout their letters they are seeking, haltingly and touchingly, to articulate and analyse their feelings towards each other in a world of strict social and sexual convention.

Like so many letters of this kind, the couple constantly skirt around the grief of war. At one point Dot asks Billy to try to find her young uncle’s grave near Couin in northern France and he reassures her of the peacefulness of the spot. There is a conversation where Dot broaches, very tentatively, how she might find out if the worst does happen to Billy, and another where she dreams of him coming home with a “Blighty” injury (serious but not fatal). The deaths of friends are reported sadly but not lingered over.

And the letters are a story in themselves. They are initially irregular, but eventually Dot and Billy are writing almost daily. They take anything from a few days to several weeks to be delivered, so their narrative is characteristically fragmented, with conversations jumping across and between letters. Sometimes there is a lull, filled by what they call “deaf and dumbs” (field postcards with pre-printed messages).

Reading such letters provokes a range of emotions. They are not historically “important” – indeed, they are in places determinedly trivial. They say nothing at all about the horrors of war, that was not why either of them wrote. But we are drawn intimately into the couple’s daily lives, thoughts and hopes – whether Billy’s reminiscences of tea parties at Aberystwyth, Dot’s of university life once the men had gone (very quiet), the disappearance of chocolate biscuits from the shops, the pilfering of Billy’s spare kit by person or persons unknown – or the mutual happiness that ends almost as soon as it has begun.

Dot would live to the age of 94. She would never marry. Her letters to Billy were returned to her after his death and she kept the complete correspondence her whole life. That, too, is a story of the war.![]()

Sian Nicholas, Reader in History, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.