Here's why it matters that Labour's governing body has moved away from the IHRA definition of antisemitism

Jeremy Corbyn. Credit: Sophie Brown - Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

15 August 2018

Writing in The Conversation, Dr Lecturer in International History in the Department of International Politics discusses the significance of the Labour party’s governing body's decision to distance itself from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance definition of antisemitism:

Reports in The Times about Jeremy Corbyn attending a 2010 event at which comparisons of Israel with Nazism were repeatedly drawn have, once again, raised questions about the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism.

Corbyn sponsored the event, held on Holocaust Memorial Day, as part of a series entitled Never Again for Anyone – Auschwitz to Gaza. An official speaker was reported to have declared that: “Nazism has won because it has finally managed to Nazify the consciousness of its own victims.”

This all came to light shortly after the Labour party’s National Executive Committee decided to distance itself from the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism. The IHRA definition specifically includes drawing “comparisons of contemporary Israeli policy to that of the Nazis” in its examples of antisemitic discourse.

But the NEC has issued new guidelines, removing this from its list of examples. In its place comes a much weaker formulation, referring to the Shami Chakrabarti report’s recommendation that Labour members “resist” Hitler, Nazi and Holocaust comparisons. This is because “such language carries a strong risk of being regarded as prejudicial or grossly detrimental to the party”.

An unfortunate tradition

Watering down the IHRA’s definition seems ill-advised, not least because Labour representatives have an unfortunate tradition of promoting and perpetuating the analogy. In May 1948, Ernest Bevin was reported by his own under-secretary of state at the Foreign Office as railing against Zionists. The staff member described how “he says they taught Hitler the technique of terror – and were even now paralleling the Nazis in Palestine. They were preachers of violence and war – ‘What could you expect when people are brought up from the cradle on the Old Testament?’.”

Bevin’s antisemitism was unusual in what was, at the time, a strongly pro-Zionist Labour party. A more calculated and systematic attempt to equate Zionism with Nazism began to appear as the result of party members’ involvement with the much more radical forms of anti-Zionist campaigning that emerged in the 1970s.

Christopher Mayhew, founder of the Labour Middle East Council (the first significant pro-Palestinian organisation within the party), did much to popularise the analogy. He wrote in 1971 that: “Germans who massacre Jews are tried and executed. Jews who massacre Arabs are elected to political leadership.” Mayhew’s response to Menachem Begin’s 1977 Israeli election victory was to remark that “it must be hard for Arabs to understand a country in which Germans who have massacred Jews are tried as war criminals while Jews who have massacred Arabs are elected Prime Minister.”

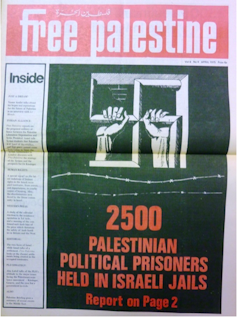

Visual representations of the Zionism-Nazism analogy also emerged in the 1970s. They were imported into British public life via Soviet propaganda and Palestinian activist networks. Free Palestine, a newsletter backed by the Palestine Liberation Organization, featured regular contributions from Labour MPs alongside controversial imagery. It even adorned the front page of its April 1975 issue with an image of a Palestinian prisoner reaching out from a prison cell window, the bars of which formed the shape of a swastika.

Ken Livingstone’s Labour Herald newspaper went on to adopt the “Zionism equals Nazism” trope with great enthusiasm in the 1980s. Perhaps the most notorious example was a 1982 cartoon which, under the caption “The Final Solution”, depicted Begin in SS uniform, standing atop a mound of bloodied corpses, making a Nazi salute.

Perhaps inevitably, this imagery brought Labour’s pro-Palestinian MPs into contact with views that one would more usually associate with the politics of the far right.

In 1987, MP Andrew Faulds received a letter from a Warley East constituent which stated that “it is readily forgotten that Jewish financiers created the German monster” and that “Judaism (Zionism) is as racially exclusive as the ‘master race’ ‘chosen people’ and just as ruthless against the Palestinian people”. Replying to this letter, Faulds made no criticisms of the overt antisemitism on display whatsoever. Instead, he thanked his correspondent for “your support for my anti-Zionist position” and remarked that it was “extraordinary how the Zionist propagandists manage to con public and international opinion”. Faulds, partly because of his public profile as a noted television actor, was an important figure in developing institutional links between the Labour party and pro-Palestinian groups such as Palestine Action.

The outbreak of the second Intifada and regular bouts of Israeli-Palestinian conflict in Gaza, saw a further spate of Zionism/Nazism analogies and comparisons in the 21st century. Corbyn himself, at a 2010 demonstration outside the Israeli Embassy in London, proved incapable of describing conditions in Gaza without making reference to Nazi Germany’s sieges of Leningrad and Stalingrad during World War II.

Livingstone, Corbyn’s close ideological ally, returned to the theme in 2005, describing a Jewish Evening Standard journalist as “just like a concentration camp guard”. Livingstone’s longstanding commitment to presenting the history of the Holocaust through the distorting lens of ideas about Zionist-Nazi collaboration was, of course, the cause of a major antisemitism crisis in the Labour party in 2016.

![]() The conclusion that this kind of imagery and language shattered the boundaries between criticism of Israel and antisemitism seems inescapable. It is within this ignoble tradition that Jeremy Corbyn has chosen to place himself.

The conclusion that this kind of imagery and language shattered the boundaries between criticism of Israel and antisemitism seems inescapable. It is within this ignoble tradition that Jeremy Corbyn has chosen to place himself.

James Vaughan, Lecturer in International History, Aberystwyth University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.