City bees' favourite flowers, according to our DNA tracking experiment

A buff tailed bumble bee emerges from a crocus covered in pollen. thatmacroguy/Shutterstock

20 February 2019

by Elizabeth Franklin, University of Guelph and Caitlin Potter, Aberystwyth University

As cities get bigger and cover more land, the need to make space for wildlife – including insects – in urban areas has become more pressing. Research has shown that cites may not be such a bad place for pollinating insects such as bumble bees, solitary bees and hoverflies. In fact, one UK study of ten cities and two large towns found a greater variety of species in urban areas than in rural areas, while another study showed some UK urban areas hosted stronger bumble bee colonies than those in rural areas.

But other research has found that cities only support the most common pollinators, such as the buff-tailed bumble bee (which is a flexible, generalist forager), and that many species decline in number as urbanisation increases.

One way to help pollinators in urban areas is to provide flowers for them to feed on, in an environment which is otherwise empty of flowering plant life. Flowers have been planted on roadsides around the UK for this very purpose.

Planting more flowers is a great idea – but it is difficult to predict which flowers different insects will use the most, and whether enough flowers are being provided for them. This is why, for our recent study, we teamed up with the National Botanic Garden of Wales to find out what some different bee species think of the wildflower strips planted by Bournemouth Borough Council.

DNA paths

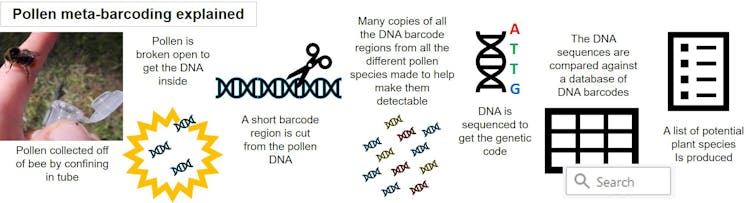

Gardeners and councils who want to plant the right flowers to attract bees usually choose them based on how easy they are to plant, and by watching which ones the insects already visit. Instead of doing this, we collected the pollen from bees who were visiting flower patches. Bees were caught and temporally held in a tube before release. The pollen that had fallen or rubbed off of the bee was used for DNA analysis to find out which flowers they had visited.

The technique we used is called DNA meta-barcoding. This allows us to look at a specific part of the plant genome and compare it to a database containing DNA barcodes for numerous British plants, created by the National Botanic Garden of Wales. This technique is relatively new and has previously been used to identify pollen in honey and pollen from the bodies of hoverflies to see which plants they had visited.

By collecting the pollen from the bee’s body, we can find out the bee’s foraging history and get samples from places where you cannot follow the bee – like up in the trees or into people’s gardens. And because it is not destructive, there is the potential to collect from an individual more than once.

But why use DNA techniques rather than simply looking at the pollen under a microscope? Well, it takes a long time to process and identify pollen grains with a microscope and DNA meta-barcoding can be done in a few days. In addition, accurately identifying pollen is very difficult even for those with a high level of expertise. The identification results from DNA meta-barcoding are also now comparable to or better than traditional pollen identification under a microscope. There are some limitations, however. In particular, DNA meta-barcoding cannot provide a count of each pollen type in a sample, only a relative proportion.

Our results show that the bees are indeed using the floral patches put out for them in cities – but these areas alone are not enough. Some of the bees’ favourite flowers in the Bournemouth sample area were purple tansy (Phacelia), chrysanthemums (chrysanthemum), poppies (Papava), cornflowers (Centaurea) and viper’s bugloss (Echium). We also commonly found that they visit garden plants, for example lupins (Lupinus), hydrangeas (Hydrangea), buddleja (Buddleja) and privet (Ligustrum), and wild plants like brambles (Rubus), sow thistles (Sonchus) and wild lettuce (Lactuca). This shows that bees travel around the urban environment to find what they need, and don’t just rely on the small floral strips planted for them. After all, bees need high quality food and variety in their diet to stay healthy, just as humans do.

Our results also showed that different bees like different things depending on their size. For example, small solitary bees are restricted to using more open flowers like daisies, while bumble bees are less restricted because they have long tongues that can reach into deep flowers. So planters need to cater for all tastes if we hope to support bee diversity.

This study only covered a tiny percentage of the UK’s pollinator diversity and there are many other insects such as hoverflies, beetles and butterflies who rely on urban flowers, too. So while the research improves our knowledge on a small number bee species’ flower preferences, there is still lots of work to do in order to make cities friendly for a wide range of pollinators.![]()

Elizabeth Franklin, Post Doctoral Research Fellow, University of Guelph and Caitlin Potter, Post-doctoral Research Assistant in Molecular Ecology, Aberystwyth University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.