Tough news for protesting farmers: Labour doesn’t actually need their votes

22 November 2024

Writing in The Conversation Professor Michael Woods from the Department of Geography and Earth Sciences discusses the proposed changes to inheritance tax relief and the affect on British farmers:

British farmers are protesting against proposals in the recent budget to change inheritance tax relief on farms. They claim the change will force many farm families to sell land in order to pay tax bills. While that is debatable, this is only the latest grievance for farmers who have had to face rising costs, volatile prices, disadvantageous trade policies and controversial post-Brexit reforms of farm subsidy schemes.

Over 20,000 protesters gathered in Whitehall on November 19 to protest the inheritance changes. They have been led to believe that Labour needs their votes for its majority, which puts them in a position of power. But does it?

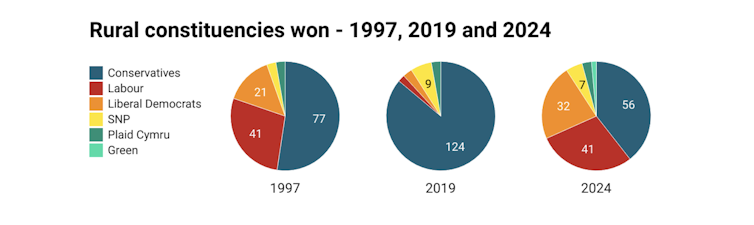

Labour won 41 of the 140 most rural constituencies in England, Scotland and Wales in July’s general election. That’s a significant increase on the three it took in 2019.

Across all rural seats, it polled 24.4% of the vote. However, rural constituencies can be won without farmers’ votes. Statistics for employment by industry are not yet known because new constituency boundaries were used in 2024. But under the old boundaries, used until 2019, there were only 16 constituencies in England and Wales with more than 5% of the workforce employed in agriculture, forestry and fisheries. Labour won just four of the main successor seats to these constituencies in the election.

A poll of 434 farmers for the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit in May found that 35% planned to vote Labour. An unscientific self-selecting internet poll by Farmers’ Guardian during the election campaign put Labour’s support at 23%.

All this indicates that probably between a fifth and a third of farmers voted Labour in July. Putting these figures together and adding in turnout, we can estimate that in rural constituencies won by Labour there were typically around 150-300 farmers who voted for the party. These are small numbers, but potentially enough to overturn majorities in marginals such as Forest of Dean, Derbyshire Dales, South West Norfolk, and Ribble Valley.

The farming lobby

We also need to take into consideration the precedent of the last Labour government. In May 1997, Labour unexpectedly won a tranche of rural constituencies, yet less than three months later, over 120,000 demonstrators joined a countryside rally in Hyde Park against a Labour MP’s bill to ban hunting with hounds.

Over the following winter, tumbling farmgate prices prompted Welsh farmers to picket Holyhead docks. Sporadic protests culminated with blockades of fuel depots in September 2000. Farmer discontent with the New Labour government deepened with the foot and mouth disease epidemic in early 2001. By the general election in June 2001 there was a widespread expectation that Labour would lose many of its rural seats.

In the event, Labour’s vote fell only marginally more in rural areas than it did overall. The party’s vote share was down by 2.3% in the top 20 farming seats, down 2.4% in the strongest hunting constituencies, and down 3.3% points in constituencies worst hit by foot and mouth disease, compared with a 2.2% decrease across Great Britain. The loss of only one Labour seat could arguably be attributed to rural discontent, in Carmarthen East and Dinefwr, gained by Plaid Cymru.

Labour cannot be complacent, though. Farmers have an outsized influence in rural areas. They have relatives, neighbours and business partners who are sympathetic to agricultural interests.

Come election time, well-attended farmers’ hustings can shape candidates’ priorities. The farm protesters’ message that Labour “doesn’t understand the countryside” could resonate with non-farming rural residents who feel ignored over issues such as housing, public transport, energy costs or planning disputes over new windfarms, solar arrays or pylons.

This happened in the general election in Wales, where farmers had been protesting since the start of the year against the Labour Welsh government’s new farm subsidy scheme, which requires farms to have 10% of land under tree cover. Welsh farmers’ discontent combined with wider rural dissatisfaction with cuts to public services and lack of investment in infrastructure, hurting Labour.

Labour’s vote in rural constituencies in Wales decreased by 1.25 percentage points, despite increasing in rural seats in every region in England and Scotland.

New Labour weathered the countryside protests in the early 2000s by directly challenging claims that it was out of touch with rural Britain. Ministers, including Tony Blair, gave speeches asserting that rural voters had the same concerns as urban voters, emphasising social justice issues, not farming or hunting. This was backed up by policies crafted by the Rural Group of Labour MPs and outlined in a rural white paper for England in 2000.

There are lessons for both sides. If farmer activists want to pose an electoral threat, they need to enrol non-farming rural residents and connect their concerns with wider issues of rural inequality. Equally, if Labour intends to overcome farmers’ opposition without political damage, it needs to be seen to take rural policy seriously and to start articulating an alternative vision for the countryside.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.